The Nick Shirley Effect: When 10,000 Investigative Journalists Can Be Anyone With a Camera

How YouTube + AI is collapsing the investigative journalism monopoly—and why politicians can’t hide anymore

Nick Shirley’s 42-minute Minnesota daycare fraud investigation garnered over 100 million views on X and sparked federal action within 48 hours. Meanwhile, 60 Minutes, still television’s flagship investigative program, averages 8 million viewers per episode. The math isn’t close. A 23-year-old YouTuber just out-reached legacy media by 12x.

But my take on this story isn’t really about the fraud, so I won’t debate whether Shirley or 60 Minutes gets its facts straight. It’s about what happens when investigative journalism becomes democratized at scale.

The Old Model Is Breaking

Traditional investigative journalism required months of work, legal teams, institutional backing, and broadcast infrastructure. A single 60 Minutes segment could take a year to produce. The high barriers to entry created a natural oligopoly. Only a few organizations could afford the overhead.

That scarcity gave legacy media immense gatekeeping power. Stories lived or died based on editorial decisions. When Bari Weiss pulled a 60 Minutes segment about Venezuelan deportees, the backlash was swift, but the story stayed spiked. The institution still controlled distribution.

Until it didn’t.

Enter The Nick Shirleys

Shirley spent days, not months, documenting Minnesota daycare centers allegedly receiving federal funds while serving zero children. His production cost: a camera phone, a rental car, and public records requests. His distribution: YouTube and X. His reach: 135 million views and counting.

Neither Shirley nor 60 Minutes gets investigative journalism exactly “right”. Both have gaps, both take liberties, both draw fire from critics. But only one format catalyzed an immediate federal response. HHS froze Minnesota childcare payments. Attorney General Pam Bondi cited Shirley’s work. DHS Secretary Kristi Noem launched raids.

The difference? Speed, scale, and the impossibility of institutional gatekeeping.

What Happens When There Are 10,000 Nick Shirleys?

Now imagine this capability multiplied. YouTube provides distribution. AI tools dramatically compress investigation timelines: document analysis, pattern recognition, data correlation that once took teams of researchers now happen in hours. Anyone with curiosity, a camera, and basic tech skills can expose what governments try to hide.

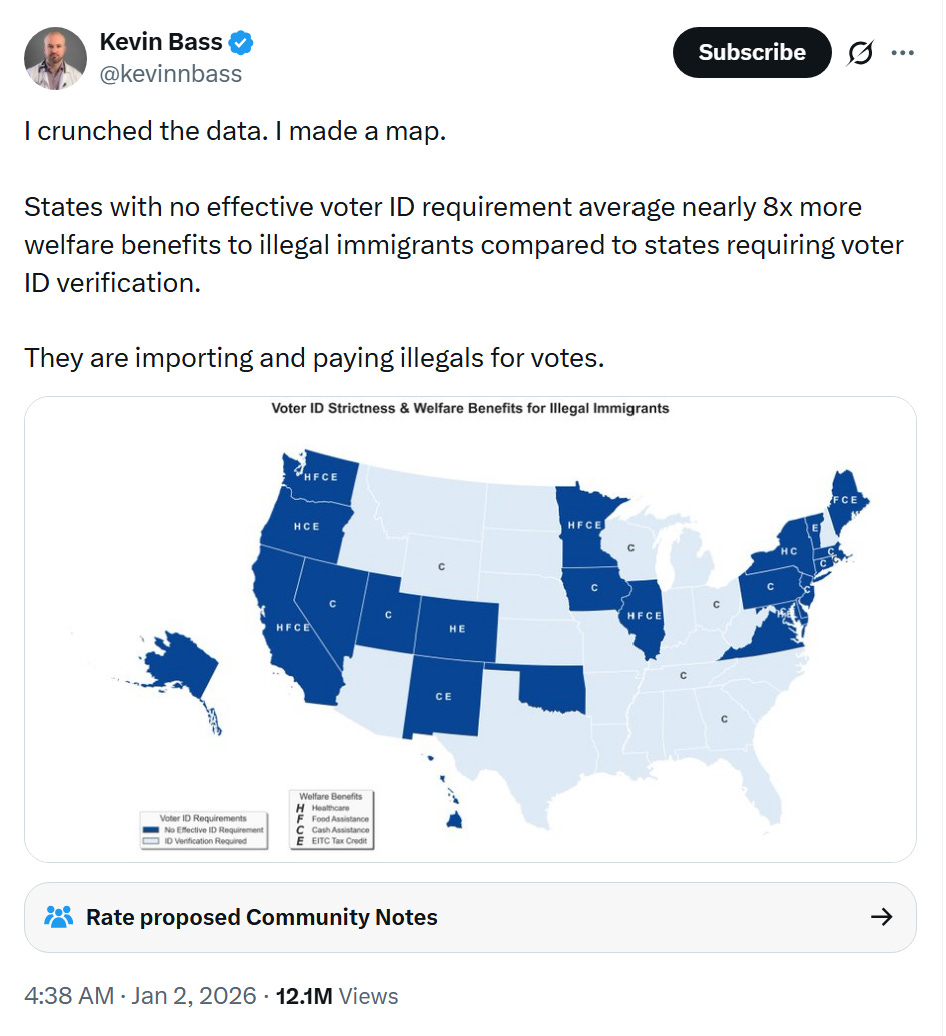

Ignoring the specific topic of voting (it’s not the subject of this post), but note that Kevin Bass dug into a topic, and in his X/thread included a link to a GitHub repo to see his code and analysis. Kevin has 180K followers on X.

Can you imagine if 60 Mins put all their notes and data into a GitHub repo for anyone to review on their own? The constraint was never investigative talent. It was access to infrastructure. That constraint just evaporated.

And Now VCs Are Funding It

The Antifraud Company, which came out of stealth in October 2025 with $5M+ from Abstract Ventures and other VCs, isn’t even pretending this is charity. Their business model: use AI to scan public data for fraud, build cases, report through government whistleblower programs, and take 10-30% of whatever the government recovers.

They’ve identified $250 million in potential fraud since launching in June. Their pitch? “The private sector can be more efficient in going through the data and finding fraud than the government itself.”

"The only one who can generate wealth in this country and in the world is the entrepreneur, not the politician... The only thing he generates is corruption."

Javier Milei

This is the industrialization of the Nick Shirley model. When venture capital starts funding fraud bounty hunters, you know the arbitrage is real. The government loses $500 billion annually to fraud. That’s a business opportunity.

Politicians Can’t Survive This

Politicians built careers assuming investigations took months and required institutional approval. Local fraud schemes thrived because exposure required convincing legacy media that the story mattered. The calculation was simple: hide long enough, and the media cycle moves on.

That calculation just broke. When 10,000 independent investigators can document, analyze, and broadcast findings to millions in days, and when VCs fund bounty hunters who profit from exposing corruption, the entire incentive structure collapses.

You can’t wait out a swarm. You can’t spike a story when there’s no editor. And you definitely can’t hide when your exposure is someone else’s payday.

Creative Destruction Hits Journalism

This is the same pattern we’ve seen across industries: artificial scarcity protected incumbents until technology made the scarcity obsolete. Taxi medallions, hotel licensing, and media broadcast licenses all derived power from a controlled supply. All collapsed when technology enabled direct distribution.

Investigative journalism is next. Not because legacy media is dying (though it is), but because the monopoly on investigative capacity is ending. The Bari Weiss controversy illuminates the tension: she understands legacy media needs reform, but operates within institutional constraints that no longer bind her competitors.

Meanwhile, Shirley operates with zero institutional approval and reaches 12x the audience. And The Antifraud Company operates with pure profit motive and venture backing.

Welcome to the era when accountability scales.

funny timing, but just stumbled upon a new (to me) disruption to investigative journalism: hedge funds posting their findings, presumably to help with their positions

https://hntrbrk.com/pbmgpo/

This thread captures exactly what I hoped the article would surface. Spencer's Jevons paradox point is sharp. Andy's fact-checking is the kind of accountability the new model needs. And the tension between them illustrates the real story.

We're watching Schumpeter's gale from inside the storm. It's messy. The content quality varies wildly. Political opportunists grab whatever amplifies their message. Some of these new investigators are rigorous. Others are reckless. That's not a bug. That's what pre-dominant design looks like.

Before Ford, there were hundreds of car companies. Most built unreliable machines. Many were outright scams. The industry was chaos. Then the market clarified. Ford didn't win because he was first. He won because he figured out the architecture that scaled: standardized parts, assembly line, price point the mass market could afford. The dominant design emerged, and the industry consolidated around it.

Investigative journalism is in its "hundred car companies" phase right now. Nick Shirley is one of those companies. So is Matt Stoller. So is The Antifraud Company with its VC-backed bounty hunters. Most will fail. Some will be exposed as frauds themselves. But somewhere in this chaos, someone is building the Ford: the model that combines reach, accuracy, accountability, and sustainable economics.

Hayek would say the market is sending signals. The 135 million views are a signal. The instant fact-checking is a signal. The political co-opting is a signal. The question for entrepreneurs isn't whether this disruption is good or bad. It's: what architecture emerges from the chaos?

Who builds the dominant design?